by Dr. James Cuffe & Emily Phelan.

Dr. James Cuffe is an cyber-anthropologist lecturing at University College Cork and Director of the Ethnographic and Human Centred Research Group at UCC. The following article was presented by Dr. James Cuffe at the Cyber Ireland South Chapter Meeting on the 16th June, 2020.

Q: As a Cyber Security community, we are all aware how important security awareness is. What are the key Human Factors that are important and how will the future way we work change these?

If I might take a few seconds just to explain what a cyber-anthropologist does as it might be something not everyone is overly familiar with. At its simplest, Anthropology is the study of human experience seeking to understand the diversity of cultures and knowledge about our world. Traditionally anthropologists would go to far-off places to conduct research but over the last few decades we are more commonly found within large organisations researching across a range of areas where human behaviour needs to be understood. In contrast to psychology we focus on groups rather than individuals and examine social and cultural motivations rather than individual psychological motivation.

A key issue facing the technology industry is insufficient understanding of human behaviour. Anthropologists favour ethnographic methods, spending long durations in close contact with research participants in real world environments to build ground up models that are locally bespoke while drawing on universal principles. We utilise an array of theories and concepts that underpin explanations of human behaviour and have predictive value.

Cyber anthropology is one of the newest sub-disciplines within anthropology, and pays special attention to online cultures and digital behaviours. My own area of research examines human’s reciprocal engagement with technologies, particularly digital and automated technologies: analysing how humans interact with technical systems and processes to create social risk.

Within cyber-physical-social security systems [CPSS] humans are not only data users and data providers- the systems themselves are designed and built by humans and therefore subject to bias and prejudices at the design stage. Examining key characteristics of human behaviours as codified within technologies is vitally important in understanding how these systems interact with users and help to recreate our world. The benefit of ethnographic research on human behaviour within the CPSS is to provide protocols to mitigate against potential risks by identifying how these risks might arise in the first place. This type of research aids in creating best practices that are customised for specific localities, cultures and companies.

The human factors of cyber security refer to the actions or events where human actions result in a security breaches. Sometimes this may be with malicious intent, sometimes innocent error and often from a lack of understanding about security needs.

Humans might now be thought of as the risk element in the cyber security triad of Cyber-physical-social systems. Some of the key human factors in cybersecurity are quite straightforward: in broad terms they include human movement, human competence, behavioural norms, and ethical principles. During the pandemic we have seen changes to each of these due to a reorientation of society’s time and space, work is no longer necessarily in the office, nor for a designated duration of time. These changes were already evident in worldwide trends such as the 4 day working week, flexi-hours, work-from home initiatives, so really what the pandemic has done is exacerbated the speed at which this trend has moved but without the supporting ecology to make it work well or in many cases make it work fairly as the lockdown has exacerbated the differential access to resources between classes: examples include recourse to childcare, to food, even to the outdoors.

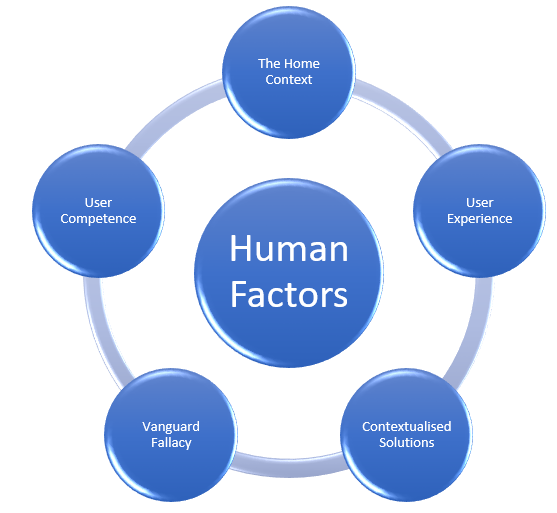

If the future of work sees more of us at home certain elements of human management are much more difficult to exact such as access to sensitive information; a company cannot control access within a person’s rented house share. At the heart of this is the blurring of boundaries – even combining of – private and public lives – under the strange juxtaposition of state care with surveillance. Not too far into the future we can see the rise of social credit systems which are in fact already here in Ireland but far more developed in China. With this in mind I have summarised 5 major elements that I think many of us will be familiar with. These elements overlap and are not mutually exclusive but by classifying them we can utilise them as a framework for thinking through future issues in the human factors around cyber security.

1: Treating the home as external vendor?

External vendors can be a security threat and it has long been important for companies to ensure that any external vendors have adequate systems security. But now – while not new – the home has an increased role as a novel external party to a company. In recent years the growth of the ‘Smart home’ has increased security risks within the home, for example devices that listen such as Amazon’s Alexa, and Apple’s Siri being an infamous recent case in Cork. Co-author Emily Phelan is actively examining this area at the moment with respect to social engineering. There is growing concern for the security and privacy of home automated systems and ‘soft-breaches’ such as family members or housemates listening in on conversations or sharing computer systems while working for different companies. can bring about data breaches. This brings in a host of new factors such as spear-phishing and friendly hacking.

2: User Experiences

UX design tries to ensure good ‘flow’ for users and establishes intuitive behavioural pathways which aim to make applications more user friendly. Operating systems on computers and smart phones are designed to allow us to swap between applications but these UX design principles can hamper security efforts as ‘flow’ reduces consciously thinking about necessary security protocols. The key problem with software being user friendly is that when you introduce security checks and gateways, they can interrupt this flow of use thereby potentially discouraging productivity and innovation. Getting the balance rights is the key concern. There is a general lack of understanding by users of complex networked systems and the use of security measures/protocols. It requires adequate support and security measures to be put in place for people working from home coupled with educational support as to when and where one should use such measures balanced against the degree of automation verses autonomy for the user. A review of platforms, regulations and protocols pertaining to individuals working from home should be carried out.

3: User Competence

A second key factor that follows on from this is the level of security competence the user has, how many of us know how to set permissions at different levels for different applications when needed. What about your children or parents? We might forget the range of access to be had through one smart phone or one laptop sitting on the kitchen table.

4: The vanguard fallacy

In our society technological progress is generally accepted as good and we tend towards technological solutionism, if there is a problem, use technology to solve it. This is despite widespread evidence of the negative effects of new technologies being pre-emptively applied to social problems and subsequently exacerbating existing problems and/or creating new ones.

It is not that new technology is inherently negative but that the full consequences of how technologies shape and change behaviour are largely unknown until after the fact. Facebook and Google are prime examples of this having grown and become mainstream under little regulation because what they were doing was so entirely new. One of the interesting proposals to remedy this is to actively automate ethical principles into new platforms and applications. When many people first hear this idea, it is abhorrent but the fact of the matter is our technologies contain many built-in biases anyway so if we were to consciously undertake to codify ethical principles it would garner far more attention and thought than it currently does. Of course in the first instance the solution is proper education and consideration before the deployment of any technologies in a social setting.

5: Generalised v particular approaches.

One of the effects of new technologies is the increased access to bespoke experiences. Family members can sit in different rooms watching different movies on difference devices. Long gone are the days of fighting between watching RTE 1 or RTE 2 on the one TV. The multitude of technological options and customisations makes it increasingly difficult for IT departments to have standardised policies. This is before attempting to deal with different role functions and now with increased working from home individuals’ personal lives increasingly need to be taken into account, what kind of bandwidth and devices do people have or do not have access to at home? We cannot (I would argue) ask employees to mould their personal lives to suit new job circumstances, this will lead to decreased productivity and increased stress; instead working conditions need to facilitate the pre-existing personal and private lives of employees but this doubles down on the generalised v particular problem, solutions cannot be one size fits all at the company, department or function level and need a more nuanced and engaged understanding of employees circumstances. Company childcare support options for the home is a clear place to start.

Summary Remarks: Incubating a Good Workforce

The security industry can only go so far in treating security as a problem that can be solved by engineering alone. Until we couple technology with a better understanding of the human users, there’s a limit on how much progress we can ultimately make. This is a key role for anthropologists to add value to existing and new ventures bringing user experience and context in the natural world into the design and planning stages.

Dr. James Cuffe is an cyber-anthropologist lecturing at University College Cork and Director of the Ethnographic and Human Centred Research Group at UCC.

James has conducted fieldwork in China on the effects of social media and technological innovation on everyday urban life and continues to research and publish on the societal effects of technology. His research team invites collaborations with industry on his current research project examining the human factor within the cyber-physical-social triad in cyber security across public, private and corporate spaces.

Email: [email protected]

Emily Phelan is a criminologist and works with James as a PhD researcher examining augmented intelligences, social engineering, and, the human construction of risk in cyber-security settings.